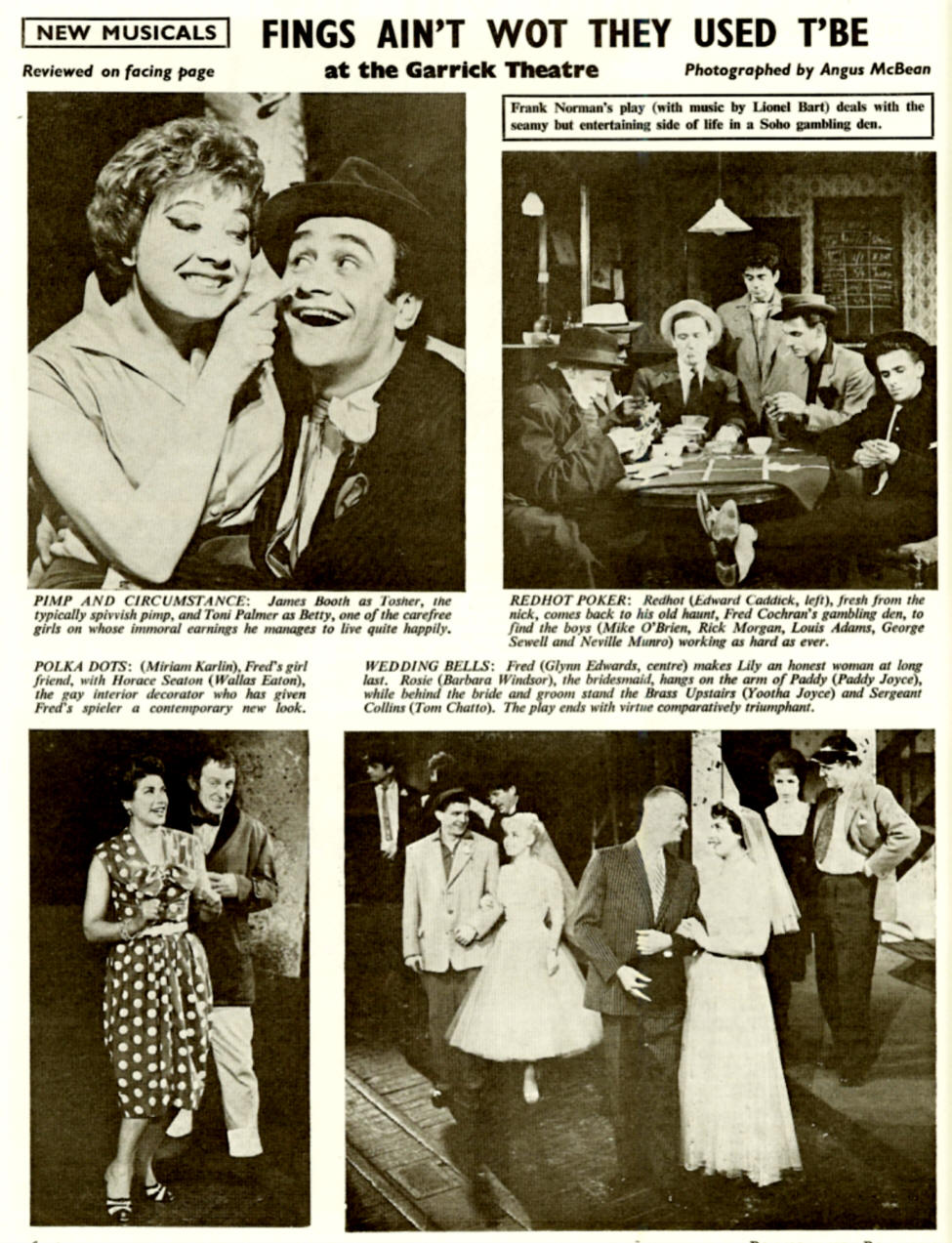

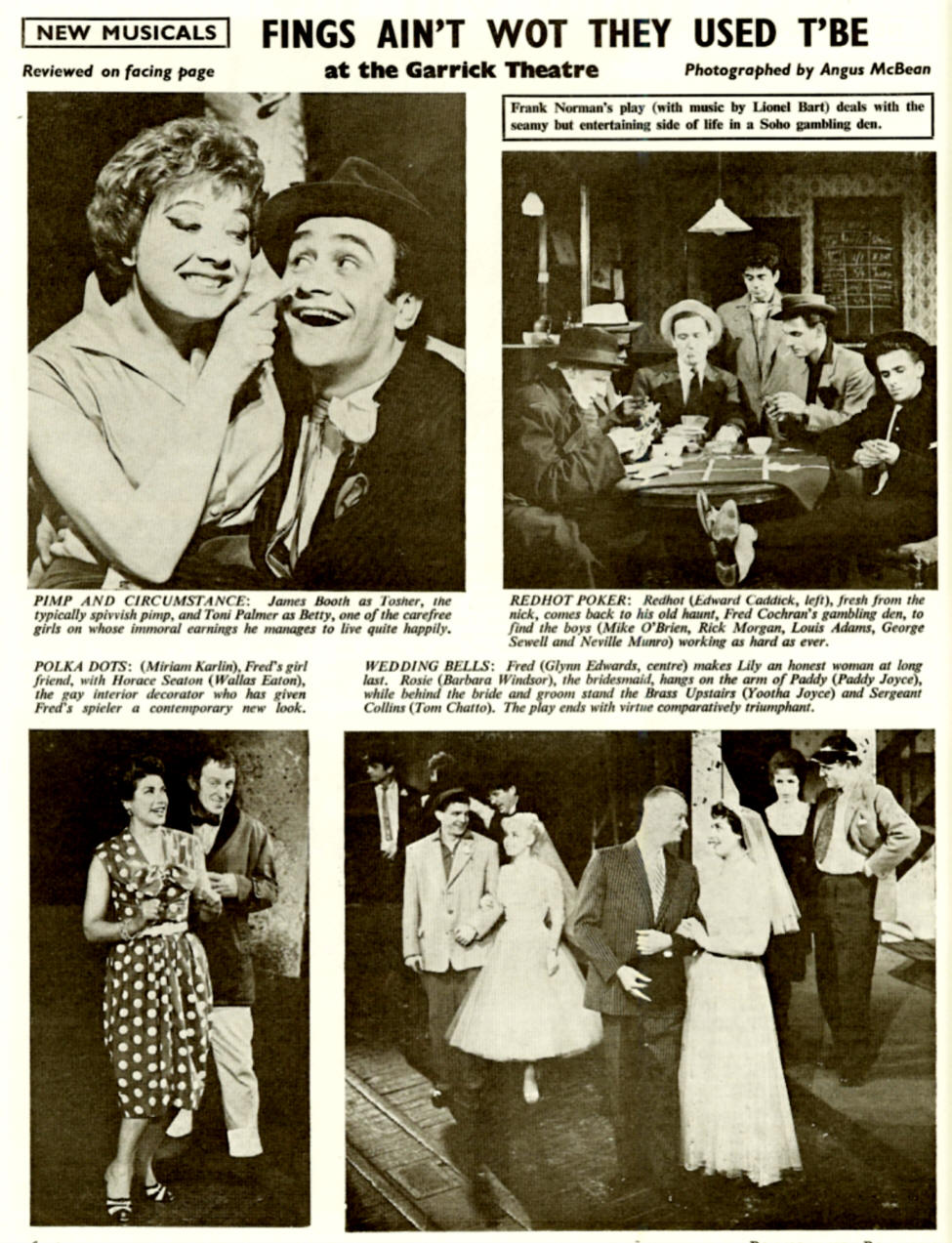

Review of Fings Ain't Wot They Used T'Be from Plays and Players, 3/60

And what did you think of Frank Norman's play-with-music-and-lyrics? Well, it is also billed simply as a musical, but that is not quite fair as it implies that Mr. Norman's contribution has been that of merely providing the "book" --the stock scenerio pegboard on which to hang a pretty assortment of songs and dance numbers. Mr. Norman's play is not nearly so ambitious and has not been hammered into nearly such significant dramatic shape as Mr. Cookson's Lily White Boys, reviewed above, but is crazy picture of life in a Soho gambling parlour is too vivid, too detailed and altogether too richly humorous to make one feel that "book" is quite the right word for it. English Damon Runyon? The golden-hearted tart, the crook who gets coy about his press-cutting book--yet, they make you think of the American. But bookish visitors might prefer to see Mr. Norman as carrying on the picaresque tradition of our own, a twentieth-century successor to Smollett, Fielding and Dickens.

Certainly the play is entertaining enough to stand on its own feet without the music. Nothing very much happens except for an off-stage razor fight between rival crooks, but the characters have sufficient depth and vivacity and the dialogue sufficient edge, with its side cracks at the new Vice Bill, the Police Force and contemporary furnishings, to hold one's attention. That is not to say that Mr. Lionel Bart's music and lyrics lack zest, bite and satire. On the contrary. The best perhaps combine all three qualities, like Where Do Little Birds Go and The Student Ponce.

But the presiding genius is Miss Joan Littlewood, whose direction has been given deservedly prominent billing. Her handling of crowd scenes is really extraordinarily skilful and this production displays the three chief characteristics of her work to fine advantage. I am thinking, of course, of topical ad libbing in the style of The Hostage (on the second night this included references to Dr. Barbara Moore and to Diana Dor's baby), of complete abandonment of the naturalistic picture fram stage convention (the cast lavish questions, asides, nods and winks whenever they can on gallery, dress circle and stalls alike) and of enthusiastic underlining of an Elizabethan directness of language that would have shocked Queen Victoria into half a century's stupor.

A monstrous charge of one shilling is made for the appallingly bad programme. Not a single photograph and not one line about the cast, the director, Theatre Workshop or Mr. Norman appears in its 16 pages. In my copy the title has been misprinted and a piece of yellow paper stuck over the error in a slovenly fashion. There is no glossary of terms used by Mr. Norman's low-life characters, which I would have thought indispensable to all except those who have either recently returned from one of Her Majesty's prisons or who have just read an account of the life lead therein in one of Mr. Norman's two books advertised in the same programme.

Stall seat visitors to the Garrick should avoid purchasing seat 024 (price one guinea) from which a part of the stage is completely masked, and they should beware of pillars elsewhere. I am beginning to compile an already impressive list of seats in London theatres from which it is impossible to see the entire stage, and would like to have precise details of others for my collection.

--Peter Roberts